If you work for a corporation, you’ve undoubtedly heard about the virtues of efficiency. And, if you’re living in America, you’ve probably noticed shortages of stables like meat, packaged food, cleaning supplies, toilet paper, and more.

What you probably don’t realize is that business’s pathological concerns for efficiency caused the shortages. And, what’s worse, most of the “expert” recommendations for dealing with pandemics will put us all at risk for precisely the same reason.

Here’s how efficiency kills and how you can fight against your company’s psychopathic drive for efficiency.

Why Farmers are Dumping Food When Store Shelves Are Empty #

A recent Fox News story explained how supply-chain efficiency and consolidation (lack of competition) has forced farmers to destroy perfect, beautiful food. At the same time, consumers can’t find a roast or tomatoes.

Dan Glickman, former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and current Executive Director of the Aspen Institute explained succinctly:

The supply chain has become very centralized, especially in meat and poultry.

Fifty years ago, there many small farmers and ranchers, many competing meat processing companies, and numerous distribution companies competing to move food (and other goods) from source to supermarket. But competition pushes prices down.

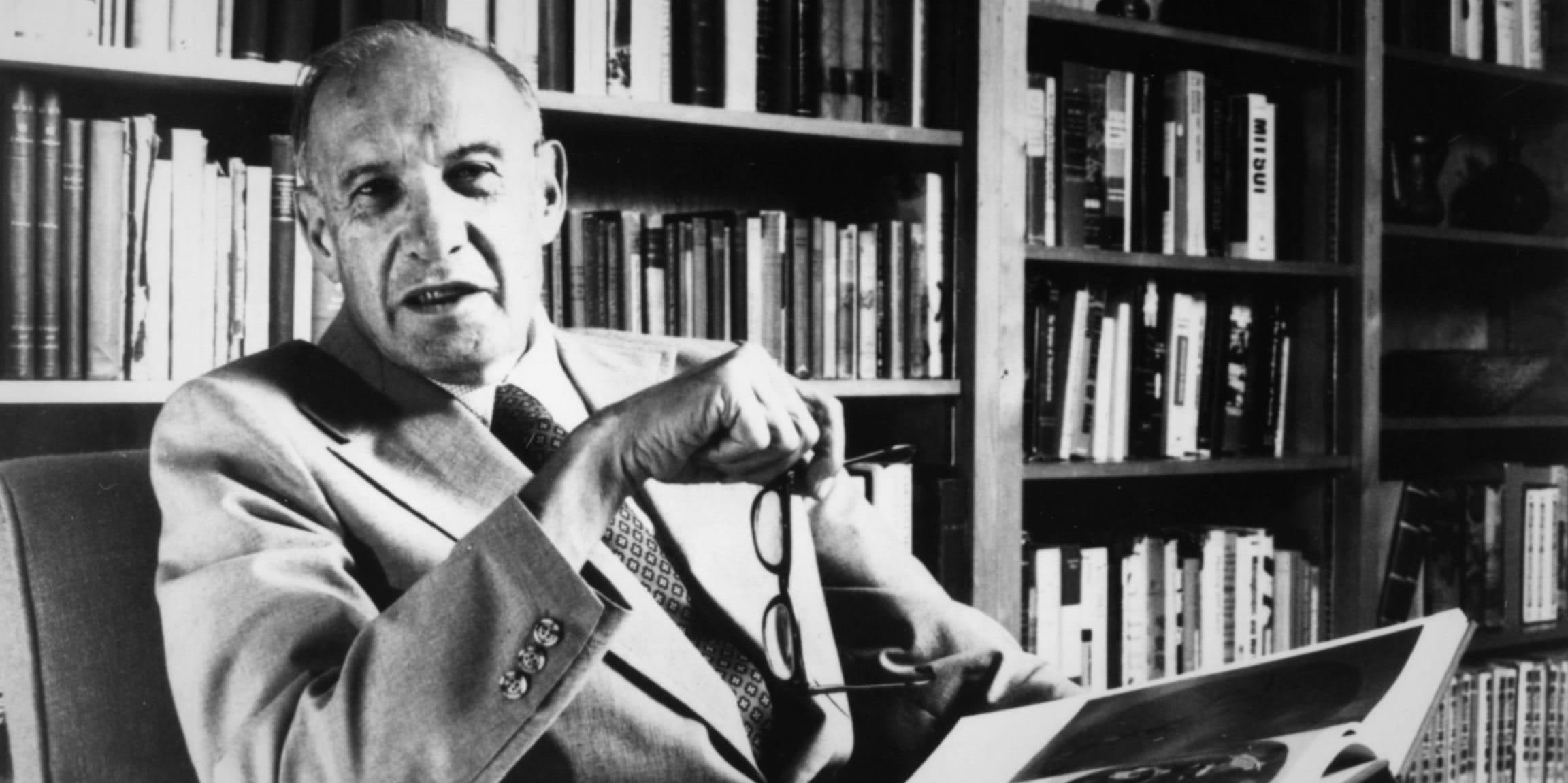

Mergers and acquisitions have always been part of business (Scrooge and Marley was, in essence, a merger of two…whatever it was that Scrooge and Marley did for a living.) But, beginning in the 1970s, mergers and acquisitions became, it seems, the primary purpose of American business. Merger mania drove business genius Peter Drucker to quip, “Executives spend so much time on mergers and acquisitions because it’s more fun doing actual work.”

The justification for M&A is always the same: “synergy.” Synergy means consolidation, not just of businesses, but of everything within the merged companies. Mergers not only eliminate jobs, but they also reduce alternative means of production and distribution. Airlines and trucking companies consolidate routes. Agricultural companies combine farms. Supermarkets consolidate stores.

These businesses also consolidate systems. Instead of four separate accounting systems, these functions meld onto one single system.

Peter Drucker

‘Executives spend so much time on mergers and acquisitions because it’s more fun doing actual work.’

All of this makes sense when it’s proposed, but business people are not immune to cognitive biases that cloud their estimation of risk. And risk is always out there. And all risks are eventually realized, even if we were never aware that risk existed at all.

The common name for realized risks that no one knew existed is “black swan.”

So, the business world’s pursuit of efficiency drove to the elimination of redundancies, which created a lot of single points of failure. It also created a very rigid, inflexible system that cannot adjust to change, even if it doesn’t fail. A screwdriver might still function, but if you need to drive a nail, the screwdriver is useless.

Food production and distribution have two main channels: one terminates with commercial buyers, and the other ends with consumers. When the lockdown came about, millions of people stopped going to work where they usually consume from the commercial channel. It isn’t just the 20 million unemployed who began staying home. It was the 40 million workers who have jobs but must work from home instead of going to an office. It’s the people who don’t have a restaurant to eat in, a library to read in, a school to sleep in, or a mall to stroll in. Almost every single American shifted over 40% of their consumption from the commercial channel to the consumer channel.

The same dual-channel system exists for almost every product you can think of: paper, canned goods, etc. Half of our production capacity sits idle even though demand has remained the same. It’s more efficient that way.

At work, you use commercial-grade food, commercial-grade toilet paper, commercial-grace coffee, and commercial-grade lightbulbs. You access Hennessy’s View view commercial-grade internet. Everything you do and use and consume at work or in the mall or while sitting in a restaurant is commercial grade.

Almost every “consumable” item you need or want must come through a channel designed, rigidly and inflexibly, to supply only half that volume. And, in the name of efficiency, that channel has zero excess capacity. Excess capacity is inefficient, you see. Businesses prefer “just in time” delivery of capacity, assuming their careful planning will always alert them to increase capacity “just in time” for a surge in demand.

All this efficiency is excellent while everything goes as planned. But, Mike Tyson said, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

Coronavirus was a punch in the mouth of the American business principle of efficiency. That’s why you can’t buy meat, poultry, fish, or toilet paper. The stiff, efficient production and distribution channels cannot adjust to change end-point demand. Efficiency and lack of competition have created a crisis.

Stiff, rigid, highly-efficient systems are incredibly fragile. They break easily. And the bigger they are, the more people get killed when they break.

How Efficiency and Consolidation Threaten Your Life #

Globalists have long sought a single world government because it’s more efficient. Relying only on the recommendations of “experts,” this one-world government would force everyone on the planet to comply with “scientific” reasoning.

In other words, globalists want to make a stiff, rigid, inflexible single point of failure system that works with fantastic efficiency and kills everyone on the planet when something goes wrong.

The latest tool of efficient extinction is Bill Gates’s universal, mandatory vaccine, without which you will be shuffled off on a highly efficient train to a concentration camp.

In a diverse, distributed, inefficient system, people could choose to be vaccinated or not. They could also want to wait and see how the early adopters of a novel vaccine respond after, let’s say, ten years. But that’s inefficient. Companies would have to anticipate demand and keep producing excess volumes in case demand suddenly increased.

It’s more efficient to force everyone to take the vaccine at once. Then you can shut down that production line and use it for some other mandatory vaccine. Efficient as sin!

Moreover, through Facebook, Google, and Twitter, the globalists have banned access to information that isn’t officially sanctioned by the one-world government. Medical and scientific studies that the WHO doesn’t not like are forbidden. You’re not even allowed to know about them. Even if the banned science is right and the WHO science wrong, you must follow the WHO way even unto death because it’s more efficient.

Globalists are building a rigid, inflexible, and fragile healthcare system that will efficiently kill us all.

How to Defy Consolidation, Efficiency, and Fragility #

Nobody likes a naysayer. But there are ways to plant seeds of doubt into people’s minds regarding the wisdom of efficiency that makes the system more fragile.

“What do you think would be the top three events that could break this system?” This question will make someone think of bad things and the consequences they impose. Maybe not on the spot, but right there. And “three” is a magic number. Most people can think of three of anything.

When we easily meet the challenge of identifying three causes of a disaster, our confidence in whatever we’re proposing slips.

Alternatively, you can shake someone’s confidence in their idea by demanding a long list of its virtues. “Gee, Bob, it sounds like you’ve put a lot of thought into this. What are the top 10 benefits we’ll get from this so I can get other people excited.” Bob will rattle off two or three benefits instantly. The fourth will sound like a stretch. He’ll give up before getting to the sixth. Emotionally, he’ll begin to question the soundness of his idea. If he, the inventor of this idea, can’t come up with ten reasons to do it, it might be a bad idea.

These little cognitive tricks might not dissuade your CFO from consolidating your company’s bathrooms in the kitchen, so you need only one set of pipes (efficiency). Still, they’ll help chip away people’s confidence in bad ideas. And, if enough people doubt an idea, the CFO might eventually question it himself.

Efficiency kills.